The Distant Mirror blog has migrated to a new web address.

The Distant Mirror blog has migrated to a new web address.

Please follow this link to read up-to-date entries! See you there!!

http://www.distantmirror.discoveryworld.org/

The Distant Mirror blog has migrated to a new web address.

The Distant Mirror blog has migrated to a new web address.

Posted in Uncategorized

July 15th-17th marked the 5th annual Eyes in the Deep program, where the public are given the opportunity to explore and document local Lake Michigan shipwrecks along Milwaukee’s lakefront. This season, Discovery World once again assembled a team of experts to showcase underwater technology in the exploration and documentation of the shipwreck Appomattox located at the end of Capitol Dr. off Atwater Beach. Our research platform for this maritime expedition was the Milwaukee Boat Lines bi-level vessel the Voyageur captained by Jake Gianelli.

This year David Thompson of Nautilus Marine Group and Portunes International brought his Proteus ROV (remotely operated vehicle), which were the primary “eyes” on the shipwreck. Built by Hydroacoustics, the Proteus 500 ROV is 28 inches long x 16 inches wide x 13 inches tall. It weighs 70 lbs (31.8 kgs) and can dive 500 ft (152 m) using on board rechargeable batters that power two forward thrusters, one vertical thruster and one horizontal thruster. With around 500 lines of resolution, the video camera can tilt 170 degrees and switch between color or black and white, making it ideal for exploring in low visibility water.

This year David Thompson of Nautilus Marine Group and Portunes International brought his Proteus ROV (remotely operated vehicle), which were the primary “eyes” on the shipwreck. Built by Hydroacoustics, the Proteus 500 ROV is 28 inches long x 16 inches wide x 13 inches tall. It weighs 70 lbs (31.8 kgs) and can dive 500 ft (152 m) using on board rechargeable batters that power two forward thrusters, one vertical thruster and one horizontal thruster. With around 500 lines of resolution, the video camera can tilt 170 degrees and switch between color or black and white, making it ideal for exploring in low visibility water.

A few weeks before this event, we had the opportunity to work with Dave and his colleague Brian Abbott of Nautilus Marine Group to map the Appomattox shipwreck using acoustic imaging called Sector Scanning Sonar. Brian has worked internationally on archaeological sites, including mapping the Titanic, so having him here was a great treat. This preliminary sonar survey was performed off the Adventure Charter Boat catamaran Mai Tai , owned and operated by Captain Rick Hake. In one weekend we successfully mapped four shipwrecks off Milwaukee.

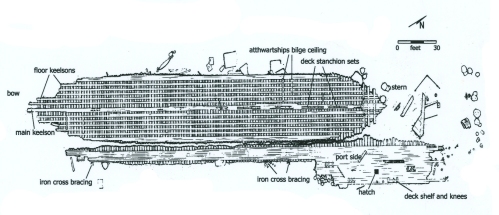

Built in 1896 at the James Davidson shipyard in West Bay City, Michigan, the 319-foot long Appomattox was the largest wooden bulk steamer ever produced on the Great Lakes, and possibly the world. With an oak hull supported by steel bracing and powered by a triple expansion steam engine, the Appomattox was a truly modern vessel by contemporary standards. She had an uneventful life on the Great Lakes until the night of November 2nd 1905, when loaded with a cargo of coal, she was blinded by heavy smog and industrial smoke emanating from Milwaukee. As a result, the Appomattox ran hard aground on a sandbar, just north of the Milwaukee Harbor entrance off the end of Capitol Drive. Unable to be freed, she was pounded in the heavy surf, stripped of valuables and eventually abandoned. Today the Appomattox rests in 15-20 feet of water with large sections of her hull still intact.

This site plan was completed by the Wisconsin Historical Society's Underwater Archaeology and Maritime Preservation Program

On Friday July 15th at 10am sharp, the Voyageur left Discovery Worlds’ dock with over 30 middle and high school students onboard, as part of Discovery Worlds’ summer camp program in Underwater Robotics and Underwater Archaeology. Several adult passengers were also aboard, as we made the forty-five minute voyage to the Appomattox shipwreck. En route, all were given a presentation about the shipwreck that was previously researched by the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Underwater Archaeology and Maritime Preservation program, as well as the Great Lakes Shipwreck Research Foundation.

Dave Thompson (left) teaches students about the ROV, while students (right) put the finishing touches on their ROVs prior to launch

Prior to arriving at the shipwreck, an auxiliary dive boat captained by Bob Jaeck left ahead of us in order to place a temporary mooring line for the Voyageur to tie off to. This was done with the help of two divers, Brian Bockholt and Charles Hudson, who then assisted in guiding the ROV into the water. To everyone’s amazement, within seconds the large shipwreck came into view on the monitors inside Voyageur. The distinguishing feature of the wreck were the large keelsons, which formed the rigid internal skeleton of the ship. These enormous oak timbers measure 1.5 feet across and over 30 feet in length.

Once we were safely on the wreck, the controls were turned over to anyone who wanted to pilot the ROV and explore the site. We were even able to talk to the divers with the aid of an acoustic earpiece that picked up our voices from a hydrophone that was lowered into the water. We spent over half an hour exploring the wreck, while the underwater robotics students got a chance to test out their hand-build ROVs. Despite some buoyancy issues, the students’ ROVs performed very well. One was even fitted with a video camera that allowed us to see the shipwreck from its perspective.

The final expedition to the Appomattox occurred Sunday morning, July 17th, once again aboard Voyageur. This time the auxiliary dive boat Mai Tai, captained by Adventure Charter boat captain Rick Hake arrived at the wreck site ahead of Voyageur in order to place the temporary mooring line for the larger Voyageur to tie off to. Once on station, I put on my dive gear and swam over to Mai Tai, where Kimm Stabelfeldt (president of Great Lakes Shipwreck Research Foundation) and Captain Rick were also ready to SCUBA dive with the ROV and help take measurements. Wearing a full face mask with a wireless microphone, I was then able to talk to the passengers aboard Voyageur and describe what the ROV and my handheld camera were seeing. Meanwhile, Kimm Stabelfeldt began drawing a section of the shipwrecks port side as I assisted with measuring. Of particular note on this dive were the six inch-wide iron reinforcing cross straps, placed inside the hull of the Appomattox when it was built, to give it extra strength. Once again, anyone who wanted to drive the ROV was allowed to do so, which made for a very memorable experience.

Overall, this year’s Eyes in the Deep went off without a hitch, which for any underwater expedition is a feat. The big unknown factor is always the weather. Even though it was quite hot, the important thing was that the lake was calm, making it very comfortable to hover over the shipwreck for over an hour. Based on the favorable feedback from the participants, it is clear that this expedition was a smashing success and one that serves as a template for future shipwreck explorations. Stay tuned for that and more hands-on archaeology opportunities offered through Discovery World’s Distant Mirror Archaeology Program.

Legacies of Milwaukee Brewing Westside Tour

Saturday, April 30th 2011 marked the third Legacies of Milwaukee Brewing tour, developed through Discovery World’s Distant Mirror archaeology program. While the two previous tours have explored Milwaukee’s storied brewing sites in the heart of the city and on the near Southside, this urban archaeology expedition focused on the historic brewery sites located throughout Milwaukee’s near Westside. This included several forgotten historic brewery sites, the behemoth Frederick Miller Brewery, the graves of two notable beer barons, as well as the former mansions of the Miller, Schlitz, Gettelman and Pabst families.

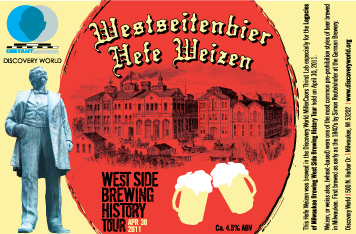

Each of the nearly fifty participants received a screen printed tote bag (printed in Discovery World’s print lab), which was filled with a custom bottle of “Westseitenbier Hefe Weizen”, brewed exclusively by yours truly for this tour in our new Thirst Lab, along with a detailed booklet outlining the chronologies for each of the sixteen sites on the tour. With Julie at the helm of a full coach bus, Leonard Jurgensen as Milwaukee Brewery Historian and I, as archaeological tour guide, the loaded Badger Bus rolled out from Discovery World just after 10am.

Each of the nearly fifty participants received a screen printed tote bag (printed in Discovery World’s print lab), which was filled with a custom bottle of “Westseitenbier Hefe Weizen”, brewed exclusively by yours truly for this tour in our new Thirst Lab, along with a detailed booklet outlining the chronologies for each of the sixteen sites on the tour. With Julie at the helm of a full coach bus, Leonard Jurgensen as Milwaukee Brewery Historian and I, as archaeological tour guide, the loaded Badger Bus rolled out from Discovery World just after 10am.

Weaving our way through a throng of pedestrians, walking in support of the March of Dimes, we quickly reached the former site of the Lake Brewery, which was established in 1841 by three pioneers from Wales. This ale brewery built at the end of Clybourn Ave. (formerly Huron St.) lasted until 1880, at which point it was razed for an expanding railroad depot. Today it is home to a Milwaukee County Transit bus garage. Rolling west along Clybourn St. and then to St. Paul Ave., the second stop was a former Schlitz “tide house” on 19th St. This three story cream city brick building was built in the late 1880s and still has a handsome Schlitz globe sign on the buildings upper cornice. Today it is home to Sobelman’s pub and grill.

Weaving our way through a throng of pedestrians, walking in support of the March of Dimes, we quickly reached the former site of the Lake Brewery, which was established in 1841 by three pioneers from Wales. This ale brewery built at the end of Clybourn Ave. (formerly Huron St.) lasted until 1880, at which point it was razed for an expanding railroad depot. Today it is home to a Milwaukee County Transit bus garage. Rolling west along Clybourn St. and then to St. Paul Ave., the second stop was a former Schlitz “tide house” on 19th St. This three story cream city brick building was built in the late 1880s and still has a handsome Schlitz globe sign on the buildings upper cornice. Today it is home to Sobelman’s pub and grill.

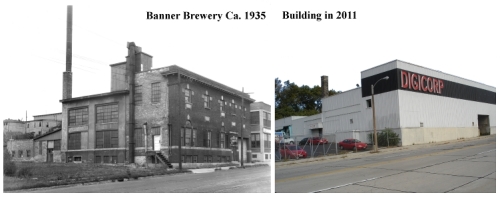

Stop three was the site of the former Banner Brewing Company (2302 W. Clybourn St.). This short-lived post-prohibition brewery opened in 1933, where they brewed primarily weiss beer at an annual capacity of 8,000 barrels. However, in 1936 the brewery ceased brewing operations for financial reasons and the brewery closed. Today the building which was built in 1919 still stands, yet most of the façade is covered with metal siding. Inside there is evidence of the original brew kettle ventilation pipe, as well as an original freight elevator.

Stop three was the site of the former Banner Brewing Company (2302 W. Clybourn St.). This short-lived post-prohibition brewery opened in 1933, where they brewed primarily weiss beer at an annual capacity of 8,000 barrels. However, in 1936 the brewery ceased brewing operations for financial reasons and the brewery closed. Today the building which was built in 1919 still stands, yet most of the façade is covered with metal siding. Inside there is evidence of the original brew kettle ventilation pipe, as well as an original freight elevator.

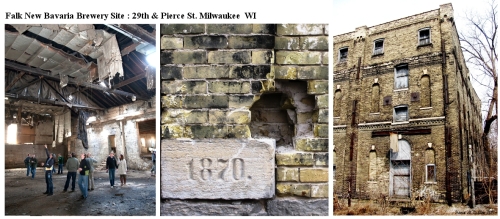

Moving on, stop four brought us to the very intriguing brewery site of Franz Falk’s New Bavaria Brewery. Located near 29th St. and Pierce St. along the south bluff of the Menomonee River valley, the property was first purchased by Franz Falk and Fredrick Goes in 1855. While brewing may have taken place there prior to 1860, there is definitive evidence that major brewing operations began there in 1870. In its heyday this brewery was one of the largest in Milwaukee, until two devastating fires destroyed the brew house and malt house in 1889 and 1892. Today the brew house is no longer standing, however the original 1870 stables and three story stock house (ice house) still stand, making them perhaps the oldest surviving original brewing related buildings in Wisconsin. They are both vacant buildings and in disrepair, however new property owners are looking to rehabilitate the structures. Prior to the tour, this archaeologist employed ground penetrating radar over the location of the former brew house (now a gravel lot). The preliminary results indicate the presence of a large foundation wall, among other evidence of structural remains.

Moving on, stop four brought us to the very intriguing brewery site of Franz Falk’s New Bavaria Brewery. Located near 29th St. and Pierce St. along the south bluff of the Menomonee River valley, the property was first purchased by Franz Falk and Fredrick Goes in 1855. While brewing may have taken place there prior to 1860, there is definitive evidence that major brewing operations began there in 1870. In its heyday this brewery was one of the largest in Milwaukee, until two devastating fires destroyed the brew house and malt house in 1889 and 1892. Today the brew house is no longer standing, however the original 1870 stables and three story stock house (ice house) still stand, making them perhaps the oldest surviving original brewing related buildings in Wisconsin. They are both vacant buildings and in disrepair, however new property owners are looking to rehabilitate the structures. Prior to the tour, this archaeologist employed ground penetrating radar over the location of the former brew house (now a gravel lot). The preliminary results indicate the presence of a large foundation wall, among other evidence of structural remains.

By 11:15am we were in route to the Miller Valley for a tour of the sprawling Frederick Miller brewery. The origin of this iconic North American brewery began in 1849, when Charles Best and Gustav Fine opened the Plank Road Brewery along what was then called the Madison, Watertown & Milwaukee Plank Road. By 1855 Charles Best & Co. foreclosed on the brewery after the Germania Bank which held the loan to the brewery went bankrupt. Meanwhile, Frederick Miller purchased the Plank Road Brewery on June 11th 1856 for $2,370. Over the following 150+ years, this brewery would grow to the immense size that it is today, covering several acres and brewing over a million barrels of beer per year. Following a guided tour through several buildings on the property, including the original lagering caves, we made our way to the Miller Inn for a delicious catered lunch and beer sampling.

By 11:15am we were in route to the Miller Valley for a tour of the sprawling Frederick Miller brewery. The origin of this iconic North American brewery began in 1849, when Charles Best and Gustav Fine opened the Plank Road Brewery along what was then called the Madison, Watertown & Milwaukee Plank Road. By 1855 Charles Best & Co. foreclosed on the brewery after the Germania Bank which held the loan to the brewery went bankrupt. Meanwhile, Frederick Miller purchased the Plank Road Brewery on June 11th 1856 for $2,370. Over the following 150+ years, this brewery would grow to the immense size that it is today, covering several acres and brewing over a million barrels of beer per year. Following a guided tour through several buildings on the property, including the original lagering caves, we made our way to the Miller Inn for a delicious catered lunch and beer sampling.

After lunch, the bus once again rolled on, this time to the little-known family home of Frederick Miller (3711 W. Miller Ln.), which was built in 1884 on a hill overlooking the brewery. An octagonal turret on the southeast corner of this wood framed Queen Anne style home stands out as a noteworthy feature. Today it is a private residence.

The next stop was a visit to Calvary Cemetery (2203 W. Bluemound Rd.) to pay our respects to the final resting place of Frederick Miller (1824-1888) and his family, as well as the grave of Phillip Jung (1845-1911), a notable beer baron who operated the Phillip Jung Brewing Company at 5th and Cherry St., between 1895-1920. A toast to these 19th century brewers was a fitting way to salute their contribution to Milwaukee’s brewing heritage.

Moving farther west, we came to the former locations of the Castalia Brewery (1893-1898) and the Wisconsin Brewing Company (1996-1998). Despite being separated by a century, both of these short-lived breweries were built in close proximity along the Menomonee River in the village of Wauwatosa (then called Center City). Only the foundations of these former breweries remain in the floodplain of the Menomonee River.

Moving farther west, we came to the former locations of the Castalia Brewery (1893-1898) and the Wisconsin Brewing Company (1996-1998). Despite being separated by a century, both of these short-lived breweries were built in close proximity along the Menomonee River in the village of Wauwatosa (then called Center City). Only the foundations of these former breweries remain in the floodplain of the Menomonee River.

The next five stops took us to the mansions built for several notable Milwaukee brewing families, four of which are located on West Highland Blvd. The Fredrick Pabst Jr. mansion, built in the Greek revival-style in 1896, still stands at 3112 W. Highland Blvd. Directly to the east (3030 Highland Blvd) is the original mansion of his brother Gustav Pabst, which was also built in 1896. Across Highland Blvd is the former mansion of the Adam Gettelman family (2929 Highland Blvd), built in 1895. Nine blocks to the east at 2004 W. Highland Blvd. stands the former home of Victor Schlitz (son of beer baron Joseph Schlitz), which was built in the Tudor-style in 1890. Finally, located at 2000 W. Wisconsin Ave. is the stately mansion of Captain Frederick Pabst, which was completed in 1892 and inspired by 17th Century English and Flemish Renaissance architecture. We were all treated to a very entertaining guided tour of the mansion, which set the stage for our final stop at Captain Pabst’s office complex and guild hall (southwest corner of 9th and Juneau Ave).

The next five stops took us to the mansions built for several notable Milwaukee brewing families, four of which are located on West Highland Blvd. The Fredrick Pabst Jr. mansion, built in the Greek revival-style in 1896, still stands at 3112 W. Highland Blvd. Directly to the east (3030 Highland Blvd) is the original mansion of his brother Gustav Pabst, which was also built in 1896. Across Highland Blvd is the former mansion of the Adam Gettelman family (2929 Highland Blvd), built in 1895. Nine blocks to the east at 2004 W. Highland Blvd. stands the former home of Victor Schlitz (son of beer baron Joseph Schlitz), which was built in the Tudor-style in 1890. Finally, located at 2000 W. Wisconsin Ave. is the stately mansion of Captain Frederick Pabst, which was completed in 1892 and inspired by 17th Century English and Flemish Renaissance architecture. We were all treated to a very entertaining guided tour of the mansion, which set the stage for our final stop at Captain Pabst’s office complex and guild hall (southwest corner of 9th and Juneau Ave).

As the bus pulled up to the 1880 castle-like complex at 4:15pm, the group enjoyed a refreshing pint in the elegant Blue Ribbon Hall (completed in 1940) as owner Jim Haertel gave an amusing historical overview of the property. This led to a behind-the-scenes tour though the dilapidated corridors of the once mighty Pabst Brewery including the former office of Captain Pabst. This led us to the original entrance to the complex and onto the awaiting bus, bringing to an end an enlightening and entertaining day of experiencing first hand several of Milwaukee’s historic brewery-related sites.

As the bus pulled up to the 1880 castle-like complex at 4:15pm, the group enjoyed a refreshing pint in the elegant Blue Ribbon Hall (completed in 1940) as owner Jim Haertel gave an amusing historical overview of the property. This led to a behind-the-scenes tour though the dilapidated corridors of the once mighty Pabst Brewery including the former office of Captain Pabst. This led us to the original entrance to the complex and onto the awaiting bus, bringing to an end an enlightening and entertaining day of experiencing first hand several of Milwaukee’s historic brewery-related sites.

Stay tuned for a future tour of Milwaukee’s historic and contemporary brewery sites located on the Northside. This tour is being planned for September 24th 2011. Call (414) 765-8625 or email reservations@discoveryworld.org to reserve your seat. Finally, you can listen to an interview about this tour recorded on 89.7FM, Milwaukee Public Radio, which aired April 25th 2011.

Stay tuned for a future tour of Milwaukee’s historic and contemporary brewery sites located on the Northside. This tour is being planned for September 24th 2011. Call (414) 765-8625 or email reservations@discoveryworld.org to reserve your seat. Finally, you can listen to an interview about this tour recorded on 89.7FM, Milwaukee Public Radio, which aired April 25th 2011.

http://www.wuwm.com/programs/lake_effect/le_sgmt.php?segmentid=7335

“Wormus speaks of the drinking of heather-beer, as one of the pleasures which the souls of departed heroes enjoyed in the society of the gods.”

(W.T. Marchant: 1888)

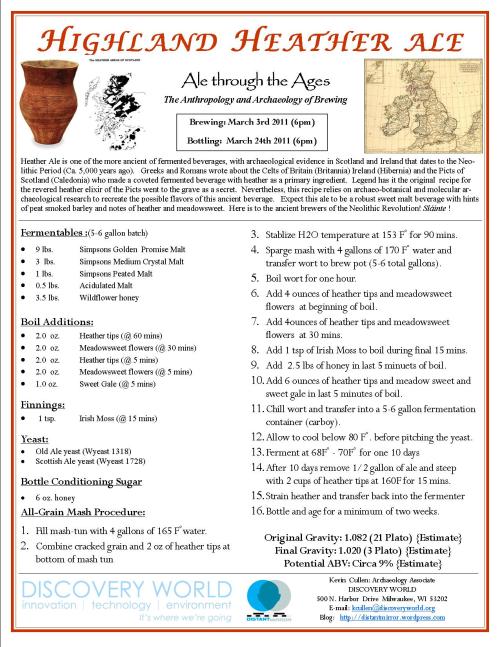

The final Ale through the Ages brewing seminar of the 2010/2011 season wrapped up March 24th here at DISCOVERY WORLD in Milwaukee Wisconsin. The challenge this time (sixteenth session) was to recreate a fermented beverage that was brewed throughout Europe’s western islands, during the Neolithic Period (ca. 6,000-4,500 years ago). This recipe is based on molecular archaeological data and pollen analysis from pottery jar fragments found specifically at several archaeological sites in Scotland.

In keeping with provenance, we used a generous amount of Scotland-grown 2-row barley malt, along with a dose of peat smoked barley, a dash of acidulated malt and finishing with several pounds of sage honey. En lieu of hops (as it was not used in the Neolithic), heather tips, meadowsweet flowers and sweet gale were infused during the boil. The final gravity for our 12 gallon batch was 1.082 / 21 Plato, making this a rare Ale. We let it ferment for three weeks with Old Ale yeast (W1318) in one six gallon carboy and Scottish Ale yeast (W1728) in the other 6 gallon carboy. The resulting concoction is a tantalizingly delicious “Wee Heavy” scotch ale with hints of peat, heather and floral esters.

More than one thousand islands comprise the European nations of the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Today the predominant ethnic groups include: Britons, Channel Islanders, Cornish English, English Gypsies, Irish, Irish Travelers, Kale, Manx, Scottish, Ulster-Scots and Welsh. Most of these islands have been inhabited for at least 14,000 years, since the end of the last Ice Age in a period know as the late Paleolithic. By around 8,500 years ago, most of the outer islands were occupied by the Mesolthic hunters and gathers.

Yet, it was around 6,000 years ago during the Neolithic Period that new waves of people moved onto the islands and brought with them grain agriculture and animal husbandry among other things. Known as the “Neolithic Revolution”, it spread new agricultural and technological traditions across the continent from East to West. Beginning in the 3rd millennium BCE pottery vessels found throughout Europe, usually in sets, indicate widespread fermented-beverage drinking traditions known by their pottery ware types: Baden ware, Globular ware, Corded ware, Bell Beaker ware, etc.

The Orkney Island group contains some of the oldest and best-preserved Neolithic sites in Europe. The Neolithic site of Skara Brae located on the main island is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Archaeological evidence indicates that brewing activities likely took place in one of the round stone structures, dating to ca. 3100-2500 BCE.

Moreover, at the site of Balfarg, Fife, in southeast Scotland, an intact Neolithic circular earth embankment (henge) now situated in the center of a housing estate, yielded some remarkable evidence of an ancient fermented brew. Residues of cereal grain and meadowsweet pollen found on pottery fragments dated to the third millennium BCE, clearly point to the adoption of a widespread tradition of the consumption of fermented beverages seen throughout Europe during this period.

Other brewing evidence comes from the site of Kinloch, on the Isle of Rum, located in the Inner Hebrides of NW Scotland. Near the village of Kinloch, a Neolithic habitation site, was discovered containing circa 4,000 year old pottery sherds. Residue of mashed cereal straw, cereal-type pollen, meadowsweet, heather and royal fern were also discovered. (Nelson 2005:12). This is interpreted to be the remains of a Neolithic fermented floral grog ale (McGovern 2009:138).

Folklore tales attribute the original recipe for Heather Ale to have gone to the grave of a Pictish elder, at the hand of the Scots around the 4th century AD. The Scot Kenneth MacAlpine resolved to exterminate the Pict people of Caledonia (Scotland) sparing the lives of all but two…an aged father and son. Both possessed the recipe of brewing the valued heather beer. Their lives were promised to be spared if they divulged the secret recipe. The father asked for his life to be spared in exchange for his sons life…the father then said…“now I’m satisfied…my son might have taught you the art, I never will…!”

Of the more than 55 breweries currently operating in Scotland, only a few have begun to brew traditional heather ales. For example, the Williams Bros Brewing Company, run by Scott and Bruce Williams, is a micro brewery based in Alloa central Scotland. Among their line of traditional ales, the “Fraoch” from a Gaelic word for “leann fraoich” “heather ale” is worth checking out. “It is a 5% light amber ale with floral peaty aroma, full malt character, a spicy herbal flavor and dry wine like finish.”

Now that we’ve come full circle with how this recipe was concocted, the resulting rare Neolithic Period-inspired Highland Heather brew is one to age for awhile. At 9% ABV, the resurrection of this robust ale will be well enjoyed when the right time presents itself for toasting the intrepid ancient brewers of Europe’s western fringe! Slàinte Mhath!

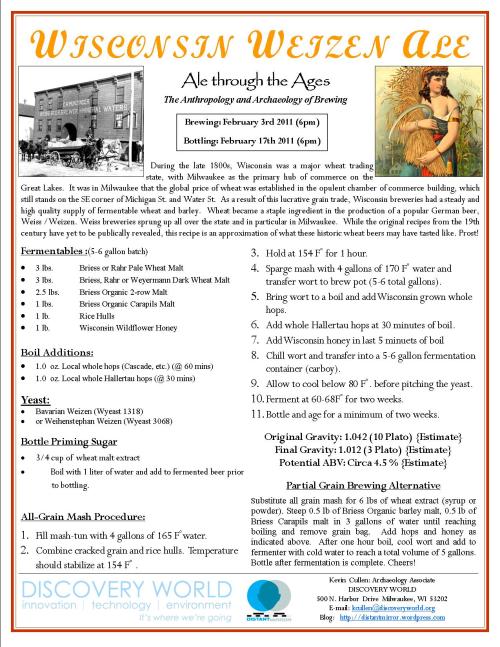

The most recent Ale Through the Ages brewing series at Discovery World focused on Wisconsin and Milwaukee’s proud brewing heritage, as we recreated a traditional wheat ale. During the late 1800s, Wisconsin was a major wheat trading state, with Milwaukee as the primary hub of commerce on the Great Lakes. As a result of this lucrative grain trade, Wisconsin breweries had a steady and high quality supply of fermentable wheat and barley. Wheat became a staple ingredient in the production of a popular German beer, Weiss /Weizen and “weiss breweries” sprung up all over the state and in particular in Milwaukee. While the original recipes from the 19th century have yet to be publicly revealed, this recipe is an approximation of what these historic wheat beers may have tasted like. Therefore, we selected local wheat and barley malts, in addition to locally grown hops, as well as Wisconsin wildflower honey. A total of 12 gallons were brewed, 5.5 of which was fermented with Bavarian Wheat yeast, 5.5 gallons was fermented with Weihenstephan Weizen yeast, and 1 gallon was fermented with a local wild strain of yeast collected by a Milwaukee home brewer and class participant, Matt Spaanam.

Wheat and Milwaukee

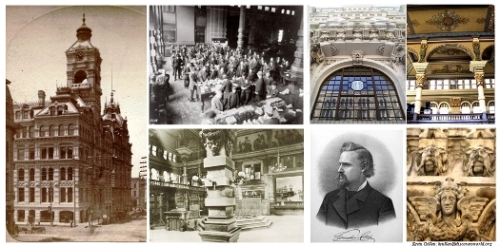

Wheat and MilwaukeeWheat (Triticum spp) is a grass species from Western Asia that was originally domesticated least 10,000 years ago, yet is now cultivated worldwide. Since the beginning of the European influx into America’s heartland, wheat has been a major crop and commodity of export to the global market. Milwaukee was one city in particular that was once at the forefront of the American and indeed global grain market. This is evidenced by the iconic Chamber of Commerce building, which still stands on the SE corner of Michigan St. and Water St. Completed in 1879 by the esteemed architect Edward Townsend Mix, it was inside this Italian Renaissance style building that the main trading rooms of the Milwaukee Grain Exchange were housed. It was here between1879-1935 that the price of wheat was set for the global market in the first “trading pit” in the country. Sadly the octagonal pit no longer survives. However, restoration of the trading room in the early 1980s resulted in preservation of one of best examples of mural-ornamented Victorian commercial interiors in North America.

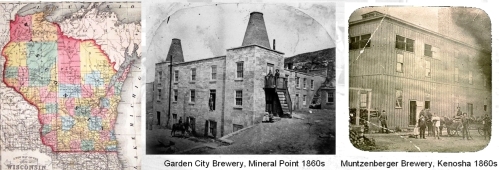

Wisconsin Pioneering Breweries

Wisconsin Pioneering BreweriesThe earliest evidence of a commercial brewery in Wisconsin opened in 1835 in Mineral Point (Iowa Co.) by John Phillips (Apps, J 1992). This region of southwestern Wisconsin saw the earliest influx of Europeans, who principally arrived from Cornwall, England and were employed in mining lead. These intrepid miners were given the nickname “badgers”, due to their burrowing tunnels, a moniker that eventually became Wisconsin’s mascot. It is likely that this pioneer brewery, as well as Rablin & Bray’s brewery in Elk Grove (Lafayette Co.) that opened in 1836, were likely brewing ales rather than lagers. Lagers would soon become the norm, once large numbers of German immigrants arrived in subsequent decades and opened their own breweries. By the end of the 1840s there were at least 22 breweries in Wisconsin. That number rose to at least 190 breweries in Wisconsin by the end of the 1850s. Towns and cities across Wisconsin would grow many industries, and breweries were no exception.

Milwaukee: “Brew City USA”

Milwaukee: “Brew City USA”Without exception, Milwaukee’s brewing industry once stood head and shoulders above most American cities. In total, at least 120 different brewing companies have been established in Milwaukee over the past 175 years, giving justification for calling Milwaukee America’s “Brew City”. The most brewing companies in operation at any one time was during the 1860s when at least 40 breweries were in the production of beer, ales, lagers and often distilled spirits.

Milwaukee’s first commercial brewery was established by Simon Reutelshofer in 1839/40, and was located at the southeast corner S. 3rd & Virginia Streets. This kicked off a tidal wave of other brewing operations that ostensibly became family businesses and wherein certain families became extremely wealthy. Without going into the entire chronology of Milwaukee’s brewing history, instead I’ll discuss just two historic Milwaukee weiss beer breweries that highlight the evolution of the industry as a whole.

Milwaukee’s first commercial brewery was established by Simon Reutelshofer in 1839/40, and was located at the southeast corner S. 3rd & Virginia Streets. This kicked off a tidal wave of other brewing operations that ostensibly became family businesses and wherein certain families became extremely wealthy. Without going into the entire chronology of Milwaukee’s brewing history, instead I’ll discuss just two historic Milwaukee weiss beer breweries that highlight the evolution of the industry as a whole.

One of Milwaukee’s early breweries that produced primarily wheat based beers was established by David Gipfel in 1843 when he purchased a small wooden framed building on Chestnut St (modern Juneau Ave.) for $400 from Wolfgang Weiss, and constructed a brewing operation. In 1851, David Gipfel’s eldest son Charles (Chas.) assumed ownership of the family brewery and renamed it the Union Brewery. In 1853 a four story Federal-Style cream city brick saloon and boarding house was built fronting Chestnut St. with the original brewery in the back. By the 1880s, the brewery was known principally for brewing weiss beer and was called the Charles Gipfel Whitebeer Brewery. However in 1890 the brewery closed due to increased competition among local breweries. The building housed various businesses over the next century, until 2007, when the building was jacked up and relocated from 423 Juneau Ave. to a vacant lot along Old World 3rd St. Sadly, in 2009 due to insufficient funding for redevelopment, the building which at the time represented Milwaukee’s oldest surviving brewery was demolished. Today it is a pile of bricks in an architectural salvage yard along the Milwaukee River.

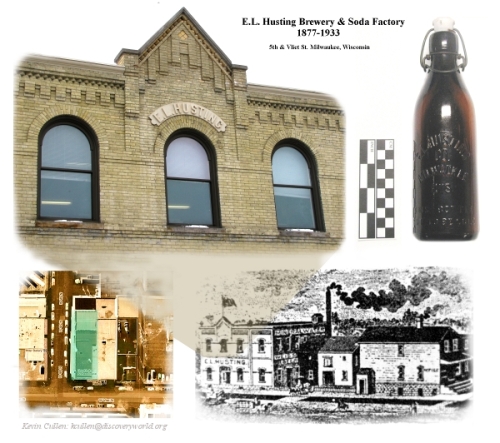

One other historic Milwaukee brewery that focused primarily on brewing wheat-based beer was Eugene Louis Husting. Like many brewers before and after him, Eugene began as a brewer at the Northwestern Brewery, which was owned by Phillip Altpeter. After marrying Phillip’s daughter Bertha in 1872, E.L. Husting opened his own weiss beer brewery and soda factory on the east side of 5th St. between Cherry St. and Vliet St. in 1877. By 1884 Husting was brewing weiss beer in an 8 barrel brew kettle and selling the product in stoneware bottles. In 1897 the Husting Brewery expanded inventory to include ginger ale, soda water, cream and orange soda, raspberry wine, and cider. As a result of prohibition (1920-1933), brewing beer discontinued and instead soda was exclusively produced. Following prohibition the company evolved into a beer and soda distributor until 1970 when the plant shut down. Today, the main building is still intact and is now considered the oldest standing complete brewery in Milwaukee. Its current tenants are a ribbon factory on the first level and Great Lakes Archaeological Research Center on the second floor, ironically the same company this archaeologist used to work for!

Wisconsin Weizen Ale

Wisconsin Weizen AleThe resulting Wisconsin Weizen ale that we brewed fermented quickly and will be bottled on Thursday, February 17th. Currently, it has a delightful wheat aroma, slightly hazy with a nice hop finish. In keeping with historic tradition, this wheat ale will be bottle conditioned, whereby adding a small amount of sweet wheat malt to each bottle in order to promote final carbonation. It should be ready to drink in two weeks, but will only get better with age. It is our hope that Milwaukee’s forgotten weiss beer brewers would be proud of this fermented concoction! Prost!

Posted in Beer Brewing, Brewing Archaeology and History, History, Milwaukee, Urban Archaeology

Tagged Beer, Brewing History, Weiss, Weizen, Wisconsin

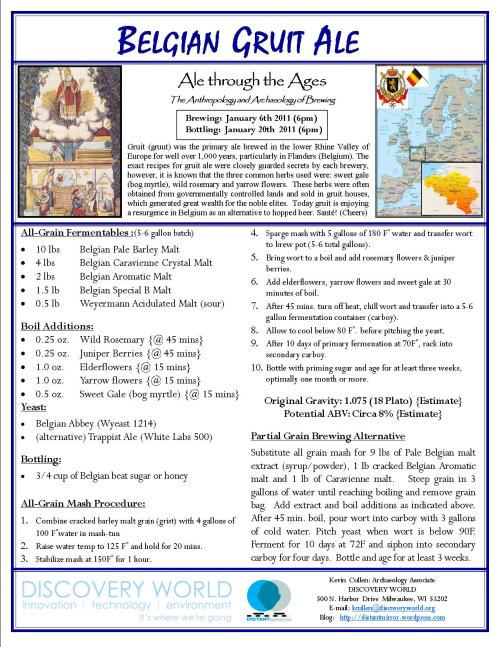

When people speak of Belgium’s brewing tradition, most would reference the unique wild-yeast fermented lambics, the sour saison’s and the high gravity trappist ales. Mention the word “gruit” and you might be greeted with a confused expression. Interestingly, gruit (gruut) was the primary ale brewed in the lower Rhine Valley and the Low Countries of northern Europe (Belgium, Netherlands, Denmark) during the Medieval Period and earlier. Today it is all but forgotten, except for a recent resurgence in certain small craft breweries in Belgium. It was this historic brew that was the focus for the most recent (and most well attended) Ale through the Ages brewing seminar at Discovery World. This high gravity (O.G. 1.068) malty Belgian ale turned out to be a splendid alternative to the traditional hopped ales of today.

En lieu of hops, gruit was a combination of a variety of herbs, which each brewery guarded with secret. The three most common herbs were Bog Myrtle (Miricia gale), Yarrow (Achillea milleflolium) and Wild Rosemary (Ledum palustr). Other later gruit additions often included: Cardamom, Caraway, Ginger, etc. Therefore, this all-grain recipe is true to the pre-14th Century Belgian Gruit style, which combined bog myrtle, yarrow, wild rosemary and juniper berries. Six gallons were fermented with a Trappist Ale yeast, while another six gallons were fermented with an Belgian Abbey Ale yeast.

Gruit Origins

Gruit OriginsLike many ancient beer recipes, the exact origin of gruit and its first use remains lost to antiquity; however, the earliest references to it come from several written sources in Flanders (Belgium) and the Neatherlands more than 1,000 years ago. By the ninth century, governments in northern Europe asserted the right to dispense of gruit in a gruuthuse (gruit house) under the imperial law known as gruitrecht. This was the exclusive authority to control the benefits from unused land, from which the bog myrtle came. This governmental right was often transferred to monasteries and nobles of Belgium, France and the Netherlands. For instance, in 974, emperor Otto II granted rights of toll, market, minting and gruitrecht to a certain Notker of Liege (Belgium) in the district of Namur. A grant to the bishop of Utrecht (Holland) in 999 also placed gruitrecht among those benefits granted by the emperor. (Hornsey 2003, Unger 2007)

The St. Peter’s Abbey was founded in 1084 by St. Arnold of Tiegem. Legend tells that Arnold, the abbeys abbot, brewed gruit ale to heal ailing builders of the abbey. Soon his reputation grew and his gruit was widely sought after, leading to his eventual status as the patron saint of Belgian Brewers. Today Steenbrugge of the PALM Brewery Group pays homage to St. Arnold with their Tripel ale that is brewed with “Gruut”, the recipe of which continues to be a closely guarded secret. Another small artisan brewery that focuses exclusively on producing gruit is the brewpub Gruut Gentse Stadsbrouwerij. Located in Ghent Belgium, they brew four varieties of Gruit ale.

In 1050 the Count of Flanders, (vassal of the French king) conquered Ename (50km west of Brussels) and built a Benedictine abbey on the ruins. The abbey became a central socio-religious enterprise in Ename for more than 750 years, until it was shuttered by the French revolutionary authorities and fell into disrepair. Excavations at the medieval abbey during the 1980s and 1990s uncovered a bakery, brewery, slaughterhouse, and other workshop. This definitively proves the written documentation that at least 1,000 years ago, formalized brewing was taking place at a large scale in Belgium. This scale reached industrial proportions by the 14th century, as evidenced by the medieval city of Bruges (Brugge), located in northern Belgium. By the late 1300s the city was brewing around 1.85 million US Gallons of beer annually (572,000 barrels). With a population of ca. 30,000, they were consuming on average 300 liters per person per year, far more than the average person today (Unger:128).

Today Belgium has around 150 breweries and brewpubs (3rd most in the EU) that produce about 800 standard beer varieties. Over 8,000 types if one-off’s are included. The total beer output for 2009 was 18 million hL (15.1 million barrels). By comparison MillerCoors produced ca. 69 million barrels the same year. The monastic Trappist brewing industry is minuscule by comparison. The combined output from the seven Trappist monastery breweries in Belgium and the Netherlands is about 0.5 million hL or 13.2 million gl. (420,000 Barrels) per year. What it comes down to, is that Belgian produced beer focuses on quality not quantity and fortunately the preservation of centuries-old styles are still being preserved for future generations. So, for those of you who are not keen on hop flavored beer, perhaps you should put gruit (gruut) on your next shopping list.

References:

Hornsey, Ian S. “A History of Beer and Brewing” 2003. The Royal Society of Chemistry

Unger, Richard W. “Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance” 2007. University of Pennsylvania Press

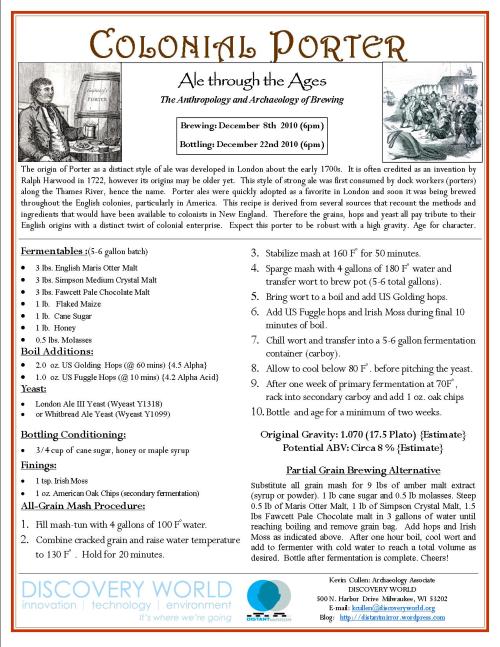

A large crowd was on hand for the fifteenth brewing session of Ale Through the Ages at Discovery World on December 8th 2010, when the historic porter brewing traditions of Britain and Northeastern United States in the 18th-19th Centuries was the topic of discussion and recreation. Once again Northern Brewer generously donated a traditional English Ale for all to enjoy during the brewing session.

This Colonial Porter recipe is derived from several written sources that recount the methods and ingredients for London-style porters that would have been available in New England during the late 1700s. Therefore the grains, hops and yeast all pay tribute to their English origins with a distinct twist of colonial enterprise using molasses, corn and maple syrup for bottle conditioning.

The invention of porter as a distinct style of ale is often credited to a Mr. Ralph Harwood, when instead of constantly mixing three types (“three threads”) of cask ales together (strong, medium and weak); he formulated a recipe combining all three types in east London in 1722. Sparging (grain rinsing) was not commonly practiced in the 18th Century; therefore, brown malts were mashed several times and drawn off separately, resulting in “strong”, “common” and “small” ales. By combining the mash running’s into one batch, this new ale became known “Mr. Harwood’s Entire” or “Entire Butt” and soon found favor with the dock workers (porter’s) along the river Thames in London. (A Butt is a British cask/vat containing 126 U.S. gallons, whereas an American Barrel = 31 gallons). A rhyme written by a J. Gutteridge around 1750 recounts Mr. Harwood’s claim to fame:

“Harwood my townsman, he invented first Porter to rival wine and quench the thirst. Porter which spreads itself half the world o’er, whose reputation rises more and more. As long as porter shall preserve its fame, let all with gratitude our Parish name”

Whether Harwood was indeed the progenitor of porter remains open to speculation, due to the fact that porter had widespread popularity across Britain by 1720s, meaning it either exploded with popularity within a couple of years, or its antecedents are older.

Take for instance the following description of porter’s popularity in England in 1726.

“…In this country nothing but beer is drunk, and it is made in several qualities. Small beer is what everyone drinks when thirsty; it is used even in the best houses and costs only a penny the pot. Another kind of beer is called porter, meaning carrier, because the greater quantity of this beer is consumed by the working classes. It is a thick and strong beverage, and the effect it produces, if drunk in excess, is the same as that of wine; this porter costs threepence a pot….” (Cesar de Saussure, October 29th 1726)

Therefore, if porter was so widely enjoyed across Britain less than four years after its supposed invention, then perhaps it was being produced earlier than is commonly accepted. Nevertheless, these original 18th Century porters were likely not black, rather they were probably mahogany in color, well hopped, with an original gravity between 1.060 – 1.070 (6-8% ABV). However, by the late 19th Century the ABV decreased to 1.040 due to the British excise tax on beer, that taxed beer based on alcohol content.

A particularly useful account of how porters were made in London during the early 1800s comes from a German chemist named Frederick Accum in his book Treatise on the Art of Brewing, which was published in 1820.

“The porter grist used by the London brewers is usually composed of equal parts of brown amber and pale malt. These proportions are not absolutely essential. An eminent establishment in this metropolis (London), the grist is composed of one-fifth of pale malt, a like quantity of amber coloured and three fifths of brown malt.”

From the earliest days of porter, it was being exported across England, Ireland and eventually to the English Colonies in America. It was being brewed in Edinburgh Scotland in 1760 and by 1773 there were three porter breweries operating in Dublin, Ireland. Beer brewing in North America can be traced to the earliest days of European settlement (ca. 1580s) in the Virginia Colonies, where corn and molasses were used as supplement fermentables. William Penn describes how beer was made in the 1680s.

“Our drink has been beer and punch, made of Rum and water. Our Beer was mostly made of Molasses which well boyld, until it makes a very tolerable drink, but note they make Mault, and Mault Drink begins to be common, especially in the Ordinaries and the Houses of the more substantial People. In our great Town there is an able Man (William Frampton), that has set up a large Brew House, in order to furnish the People with good Drink, both there and up and down the River.”

It took nearly one hundred years after Penn established his brewery for porter to be brewed in Pennsylvania. That credit is given to two London expatriates, Robert Hare Jr. and J. Warren, when they began brewing porter in Philadelphia in 1774. This was likely the first porter ever made in America and soon became favored by George Washington. He writes the following in 1788 “I beg you will send me a gross of Mr. Hairs best bottled Porter. If the price is not much enhanced by the copious droughts you took of it at the late procession.” Unfortunately, the original brewery was destroyed by a fire in 1790, yet, this brewing lineage lived on and evolved into the John F Betz & Son Inc. which survived until 1939.

George Washington wasn’t the only president with a pension for porter. Thomas Jefferson favored Philadelphia made ales and porters, particularly from the Henry Pepper Brewery (Heinrich Pfeiffer). In order to maintain a steady supply of ale and to generate revenue at his estate in Monticello NY, he enlisted the help of a shipwrecked English brewer, Captain Joseph Miller, to establish a brewery there in 1818.

At the dawn of the 20th century, East Coast breweries continued manufacturing porter, in addition to breweries across the country. Anheuser-Busch, Coors and at least 22 other breweries regularly produced porter west of the Mississippi by the early 1900s. Milwaukee’s own Schlitz Brewing Co. regularly made porter. So too did Brandon & Beal (Leavenworth, Kansas), Imperial Brewing Co. (Minneapolis, MN), August Buehler Brewing Co. (The Dalles, OR), Seattle Ale & Porter Co. (Seattle WA), Robert Witz Brewery (Sitka, Alaska), among others.

Therefore, as porter’s popularity waned in England during the 20th century, America maintained the tradition, where by the end of the century thanks to the micro brewing revolution of the 1980s, nearly every craft brewery offers at least one version of a porter. Meaning, we can all be thankful this distinct style of ale will be with us for generations to come.

In all, 12 gallons of Colonial Porter were brewed. Tipping a hat to the traditional method of combining the mash runnings, one 6gallon carboy contained the first running, with an original gravity of 1.080 (20 Plato) {recent final gravity of 1.022}. The second 6 gallon carboy contained 3 gallons of the first running and 3 gallons of a second mash rinsing, to produce a moderate strength porter, with an original gravity of 1.060 (15 Plato). After adding one ounce of oak chips to the fermenters in the secondary fermentation stage, the resulting oak flavor should come through in the flavor profile as the porter ages in the bottle. This ought to be a very nice porter indeed and ideally an accurate rendition of the first porters brewed in North America, when the yoke of English colonialism was thrown off!

The second recipe we brewed during this season’s Ale through the Ages at Discovery World was a traditional Grätzer Ale. There was great crowd on hand to participate in this brewing session to learn about the origins of this enigmatic smoked wheat ale. Grätzer is the German name derived from the town of Grätz, formerly in western Prussia. Today this town is known as Grodzisk, located in the province of Wielkopolski in western Poland. Therefore, this style of smoked wheat ale is known as Grodziskie (Grodzisz) in Polish.

The history of brewing in Western Prussia is quite extensive. For instance, during the 15th Century in the port town of Gdansk on the Baltic Sea, the city’s output of beer was ca. 25 million liters (6.6 million gallons) (ca. 210,000 barrels). Indeed in the year 1416, 378 breweries were in operation (Unger 2004:121). The Posnań district of western Poland also has a deep brewing tradition, most notably as the birth place of Grodziskie smoked wheat ale. In 1890s Poznań (Posen) had 158 breweries, 101 of which were ale breweries producing between them 177,038 hl (148,471 Barrels) (4,676,849.2 US Gallons). The other 57 breweries were lager breweries producing 307,800 hl. (258,134 Barrels) among them. Hence, lager production accounted for 63% of the total output from Posnań, compared to 37% for ale production (Zeitschrift für das gesammte Brauwesen 1894, p.23).

In the town of Grodzisk (Grätz) alone, there were five breweries in operation in 1900. While several styles of beer were being produced in Grodzisk, the most distinct was the Grodziskie smoked wheat ale. Sadly, in 1994 the large Grodziskie Brewery closed when it was bought by local rival Lech Brewery, which ostensibly ended the commercial production of this style of beer in Poland.

According to legend, the popularity of this type of beer is associated with the Benedictine monk Bernard of Wąbrzeźno (1575-1603). After blessing a dried well in Grodzik, it eventually refilled, which allowed brewers to produce their famous Grodziskie smoked beer. Moreover, Jedrzej Kitowicz (1728-1804) wrote in A Description of Manners under Augustus III the following: “Grodzisk was famous and increasingly after the Greater Poland (mid 15th century)…(Grodziskie) is a thin and tasty beer…doctors which prohibit all alcoholic beverages to patients permit drinking Grodziskie beer.”

Traditional Grodziskie is produced by smoking wheat malt with oak or beech wood. This I had to do myself on a grill, as smoked wheat malt is difficult to obtain. I cut out the base of an aluminum foil tray and stapled metal mesh screen to the bottom, in order to allow the smoke to filter through the grain bed. After letting the wheat malt soak in water overnight, it was ready to be placed in the smoker. I used wet oak placed over a low flame to produce a heavy smoke atmosphere in which the wet grain was subjected to for a minimum of three hours.

Once the smoked wheat malt was dry it was time to grind it and get it ready for brewing. Given the large number of participants in this brewing session, we brewed 10 gallons of Grätzer. This required 20 lbs of wheat malt, 16 lbs of which was oak-smoked. The mash stabilized at 150F for 40minunts before the program began. We sparged the mash with 180F water and brought the wort to a rolling boil. Polish Marinka hops, Hallertau Mittelfruh and German Spalt hops were added throughout the boil. Once the wort was cooled one five gallon carboy was fermented with German Ale/Kolsh yeast from White Labs, while the other was fermented with German Wheat yeast from Wyeast.

Once the smoked wheat malt was dry it was time to grind it and get it ready for brewing. Given the large number of participants in this brewing session, we brewed 10 gallons of Grätzer. This required 20 lbs of wheat malt, 16 lbs of which was oak-smoked. The mash stabilized at 150F for 40minunts before the program began. We sparged the mash with 180F water and brought the wort to a rolling boil. Polish Marinka hops, Hallertau Mittelfruh and German Spalt hops were added throughout the boil. Once the wort was cooled one five gallon carboy was fermented with German Ale/Kolsh yeast from White Labs, while the other was fermented with German Wheat yeast from Wyeast.

Traditionally isinglass was used in Northern Europe and Britain to accelerate the clarification (fining) of cask-conditioned ales. Isinglass is a fining that is produced from sturgeon bladders, which causes the live yeast to flocculate into a jelly-like mass that settles to the bottom of the cask. For optimum performance, the beer must be fined at the coldest point in the process (ca. 50 F). This was done during during secondary fermentation, at which point the carboy was chilled outside (40-55 F).

Traditionally isinglass was used in Northern Europe and Britain to accelerate the clarification (fining) of cask-conditioned ales. Isinglass is a fining that is produced from sturgeon bladders, which causes the live yeast to flocculate into a jelly-like mass that settles to the bottom of the cask. For optimum performance, the beer must be fined at the coldest point in the process (ca. 50 F). This was done during during secondary fermentation, at which point the carboy was chilled outside (40-55 F).

The results of this traditional Grätzer are quite pleasing. At 4% ABV this smoked wheat ale slightly hazy with distinct smoky notes and a crisp hop finish.

The results of this traditional Grätzer are quite pleasing. At 4% ABV this smoked wheat ale slightly hazy with distinct smoky notes and a crisp hop finish.

It would be a shame for this ale to fade into the ether like so many other lost styles. Fortunately there a revival may be taking place in Grodzisk Poland. In August of 2010, a home brewing competition was held during the 31st International Breweriana Exchange called, “Almost like Grodzisz.” The goal was to recreate and revive the legendary Grodzisk beer brewing tradition, which was judged by former Grodziskie Brewery workers. Perhaps this is incentive to maintain the longevity of this very old style of ale for generations to come. Na Zdrowie!

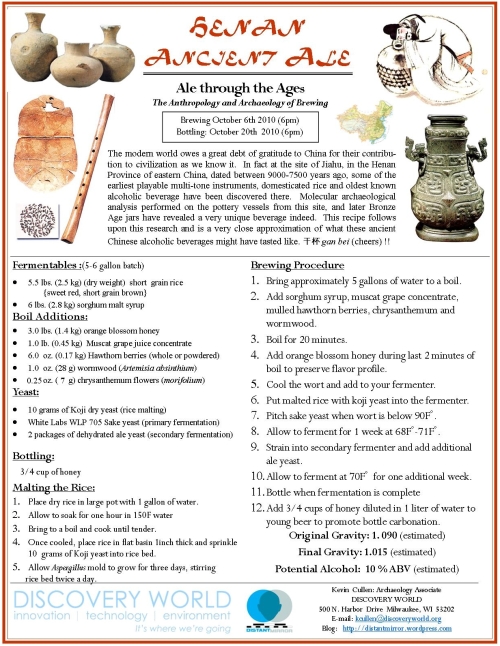

Now in the third season of the Ale Through the Ages brewing series here at Discovery World, the latest brew turned out to be one of the most challenging and unique fermented beverages we’ve attempted thus far. The challenge was to brew as authentic a version as we could of the oldest known fermented beverage in the world, found at the site of Jiahu in the Henan Provence of eastern China, which turned out to be at least 9,000 years old!

The following recipe for a 5 gallon batch of Henan Ancient Ale as I’ve dubbed requires first malting the rice using Aspergillus mold (Koji) much like making Saki, followed by the use of Saki yeast to begin the initial fermentation, followed by a basic ale yeast to complete the fermentation. The use of three separate yeast strains was necessary to convert this high gravity ale in only two weeks of fermentation. Not surprisingly Dogfish Head Brewery has also previously recreated a limited batch based on this ancient beverage, which they call Chateau Jiahu. While they stayed true to the research by using honey, muscat grapes, hawthorn fruit, and Chrysanthemum flower, they deviated by using barley malt as the primary fermentable. I like to think this recipe without barley is an even more accurate recreation. Nevertheless, there is a great interview about Dogfish Head’s recreation on NPR that aired in July of 2010.

The modern world owes a great debt of gratitude to China for their contribution to civilization as we know it. For instance at the site of Jiahu, in the Henan Province of eastern China (east of Fuliu Mountains in the fertile Huai River basin), some of the earliest playable multi-tone instruments, domesticated rice and oldest known alcoholic beverage have been discovered there. The site was discovered in the 1960s, but only in the past 15 years have significant excavation activities begun. Jiahu is 55,000 square meters, yet only about 5% of the site has been excavated. Thus far 45 house foundations, 370 cellars, 9 pottery kilns, dozens of burials and thousands of artifacts of bone, pottery, stone and other materials have been found. Radiometric dating proved that the site was occupied between 9000-7500 years ago in a period known as the Chinese Neolithic.

Molecular Archaeological Analysis of pottery sherds from domestic contexts was performed by Dr. Patrick McGovern (University of Pennsylvania) among others, using Gas and Liquid Chromatography, Mass Spectrometry, Infrared Spectrometry and Stable Isotope Analysis. Compounds identified include those for hawthorn fruit and/or wild grape, beeswax associated with honey, and rice. The results published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences hit the archaeological community and global media by storm.

Following the Neolithic Period, there is much more evidence of ancient alcohol during the Chinese Bronze Age, specifically during the Shang 商 Dynasty (1600 BCE and ca.1050 BCE). The reason for this is because preserved alcoholic beverages have been excavated in many burial tombs in the Henan Province such as at Fuhao, Jiazhuang and Changzikou. These bronze vessels were hermeneutically sealed with lids after thousands of years in the ground. In fact. inside a tomb at Changzikou, 52 bronze lidded vessels were discovered, which still contained the original liquid rice wine. Subsequent analysis of these beverages showed that wormwood, chrysanthemum, and/or tree resins (e.g., China fir and elemi) had been added, perhaps as preservatives or flavorings. Surprisingly after 3,000 years they still smelled and tasted very good!!

Du Kang (the father of Chinese alcohol) living during the Xia 夏 Dynasty (2100-1600 BCE) and is credited with first discovering alcohol by accident. The story relates how Du Kang stored some cooked Chinese sorghum seeds inside a hollow tree stump on a winter day. In the spring of the following year, a fragrant aroma wafted from the tree stump into the nostrils of Du Kang. Afterwards, Du Kang found that it was the fermented sorghum seeds which gave off the alluring fragrance. It was this node to Du Kang that I decided to use malted sorghum instead of barley malt in this ancient Chinese recreation.

The results of this experimental archaeological fermented concoction were surprising indeed. After vigorously fermenting for two weeks and undergoing four racking episodes to clarify the suspended yeast and rice, the time came for bottling this Henan Ale on October 20th. The original gravity was 1.084 and final at bottling was 1.014, meaning it was already at 9% ABV before bottle conditioning with 1 cup of wildflower honey. To all of our astonishment it tasted just like fermented grapefruit wine! I think the reason for this was the combination of hawthorn berries and the bitter wormwood. Everyone seemed to enjoy this session and all were rewarded with at least three take home samples apiece, which are sure to age splendidly and continue to render a powerful punch that is perhaps an accurate rendition of the authentic ancient alcoholic beverages brewed in this region of eastern Asia 9,000 years ago!干杯 gan bei “cheers”!

Posted in Anthropology, Beer Brewing, Brewing Archaeology and History, History, Milwaukee, Public Archaeology

Tagged Archaeology, Beer