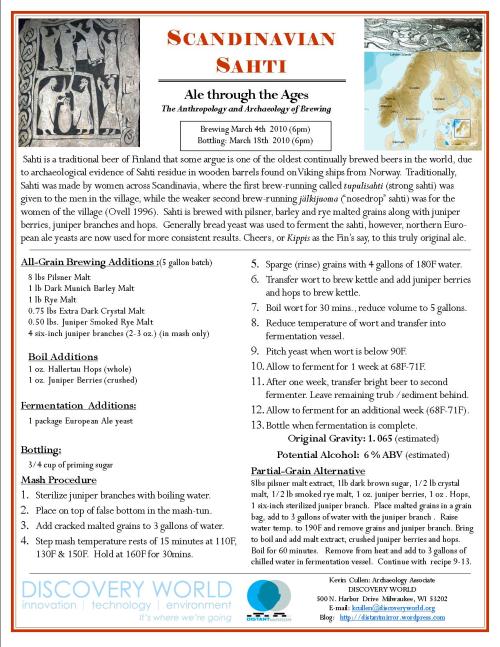

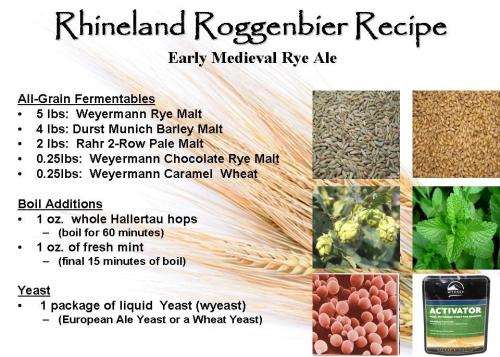

During the final Ale through the Ages brewing session of the season we brewed a Scandinavian Sahti on March 4th. This recipe is inspired by the traditional style still being brewed in Finland today. This was an all-grain batch where we used Pilsner Malt, Rye Malt, Crystal Malt, as well as a small amount of specialty grains that I had previously smoked over pine and juniper boughs. Once we transferred the wort from the mash-tun to the boil kettle, juniper berries and Hallertau hop cones were added. However, one exception was made to the traditional Sahti-styles, we used a European Ale yeast to ferment the beer, rather than the normal bread yeast. This was to ensure a complete fermentation and a bit more carbonation than the usually less carbonated Sahti’s of Finland. Our specific gravity prior to pitching the yeast was 1.072, so, we should expect this sahti to ferment out to around 7% ABV. At the moment it is bubbling well and should settle down in a few days, at which point I’ll transfer into another fermenter to remove the remaining sediment, before bottling on March 18th.

The Anthropology and Archaeology of Scandinavia

The current population of Scandinavia stands at around 23 million. It is comprised of distinct linguistic and cultural communities with proud and enduring traditions. Humans first entered into southern Scandinavia during the upper Paleolithic (ca 10,000 years ago) where they used stone tools to hunt and forage for wild foods. The earliest evidence of pottery and agriculture comes from the Ertebølle Culture who lived in Neolithic Period, which began in 5th millennium BCE. Overtime, people began using copper and eventually bronze, which defines the Nordic Bronze Age (ca.1800-500 BCE). This period is characterized by the use of bronze and long distance maritime trade of Amber to the Mediterranean region. By around 2500 years ago, the introduction of Iron marks a new cultural revolution with increased contact and influence with northern European cultures, particularly Germanic tribes. However, one of the most iconic Scandinavian cultural periods began around 1200 years ago with the rise of the Vikings. These marauding men would eventually consolidate power and spread their influences (for better or worse) across much of Europe.

The Origin of Sahti

It is in this period that we look to for evidence of the kind of ale people were consuming in this part of the world. In fact, the word “ale” is likely derived from the Viking word “aul”. Moreover, the Swedish word is öl, the Finnish olut, the Danish and Norwegian for ale is øl. One ale in particular that seems to have great antiquity in Scandinavia and particularly in Finland is a beer called Sahti. Sahti was traditionally made by women Brewster’s in nearly every village in Finland, some say for more than one thousand years. It traditionally contained malted barley, malted rye, juniper boughs and hops. Generally, saunas were used to kiln dry or smoke the malted grains (Sysila 1998).

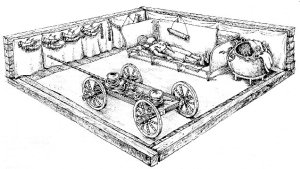

Archaeological evidence for Shati comes from the remains found inside of a wooden barrel that was placed in an elaborate Viking ship burial in Oseburg Norway that dated to ca. 800. The ship was excavated in 1904 by Professor Gabriel Gustafson of the University Museum of Antiquities in Oslo. Other sahti barrels were also found on a sunken Viking wreck off Norway in the 1930s. The design of the barrels was dated to the 9th century (Asplund:25)

The earliest known Finnish references to beer date to 1366, when it was noted that a large quantity of Sahti was consumed during the burial of a Bishop Hemminki. Moreover, the Finnish epic known as the Kalevala contains 400 stanzas related to brewing. The exact age of the Kalevala is uncertain, but many believe it was an oral tradition passed down since the Iron Age, before being first written down in 1835 by Elias Lönnrot.

Traditional Methods of Brewing Sahti

There were often two brewing cycles: The first was called tupulisahti (strong sahti) for the men and the second called jälkijuoma (nosedrops) i.e. weak sahti for the women (Ovell 1996). During the brewing cycle, juniper boughs are placed at the bottom of a hollowed out aspen log called a Kuurna, which is basically a lauter tun for extracting the flavors of the juniper and sugars from the malted grains. The bottom of the Kuurna is lined with rung-like straight pieces of wood to create a false bottom. One end of the Kuurna is fitted with a bunghole at the level of the bottom for draining the wort. In this rendition of Sahti, we placed fresh boughs of juniper at the bottom of our mash-tun.

While it took some time before we could drain off the wort through the juniper boughs, we were able to generate at least 8 gallons of shati that is sure to be delicious! Now all we need are a couple of drinking horns and we’ll be right back in Viking Period. We promise to keep the marauding to a minimum!

References

Peter Ovell 1996: Finland’s Indigenous Beer Culture

Ilkka Sysila 1998: Sahti: A Remnant of Finland’s Rustic Past